William Greenwood (1721-87), Dublin, New Hampshire.

All photos by the author

When the pandemic arrived, my wife Carolyn and I had had practice for staying at home and avoiding other people. Following her chemotherapy and a bone-marrow transplant some years earlier, we learned much about in-house quarantine for more than a year. There were books, early Netflix (good old films on DVD, delivered by the postman), plus sewing and writing projects. We took rides in the car, although we could not go into any place–no shopping of any kind for my serious cook of a bride. So, when we again faced restriction because of Covid a few years later, we imagined the pandemic’s restrictions were analogous to living in East Germany before the Berlin Wall came down: We were reasonably safe to go on about our lives, but there would little excitement. Covid ennui.

Because more than a million Americans died, the pandemic was more than inconvenience, more than working via computer screen, and more than a curtailing of travel. It was about death. Our own history should have taught us about the tragedy of big swaths of death. Just think of the first winter at Plymouth, New England’s year without summer in 1816, the potato famine that drove so many Irish to our shores, the post-World War I influenza epidemic, and of polio, infant and maternal deaths, and abbreviated life spans.

“In Death’s cold arms our bodies lives …” 1800, Wiscasset, Maine.

One only needs to wander an old graveyard to confront the specter of early and unpredictable death. The New England graveyard from the late 17th to early 19th century displays remarkable funerary art, as unsophisticated stone carvers embellished slate slabs with skulls, bodiless angels, and quaint misspellings. These powerful images form one of the outstanding chapters of American artistic expression. Even so, these markers are still reminders, as so many early stones declare, “As you are now, I once was; As I am now, you will be.” The cemetery on Star Island in New Hampshire’s Isles of Shoals contains the resting places of three young daughters of the minister, all of whom died of diphtheria within a few days of each other. Nearby is a memorial to the village’s teacher who was washed out to sea.

.

Mrs. Sarah, wife of Capt. J.N. Lord. AE. 22 yrs. & her infant son & daughter. 1862.

West Brookfield, Maine. By the mid-19th century sentimental images have supplanted the grim reaper tropes.

The style of stones evolves a little over the generations, with slight progression from primitive child-like expressions to more polished representations; carvers can be differentiated. Concord, Massachusetts has an extensive necropolis, known for its burials of the 19th-century literary lights, such as Thoreau, Hawthorne, and Emerson, as well as Victorian statuary. But the earliest part of the town cemetery is rich in angels of death and the flat skull faces.

Mary Meriam, 1621-1693. Concord, Massachusetts.

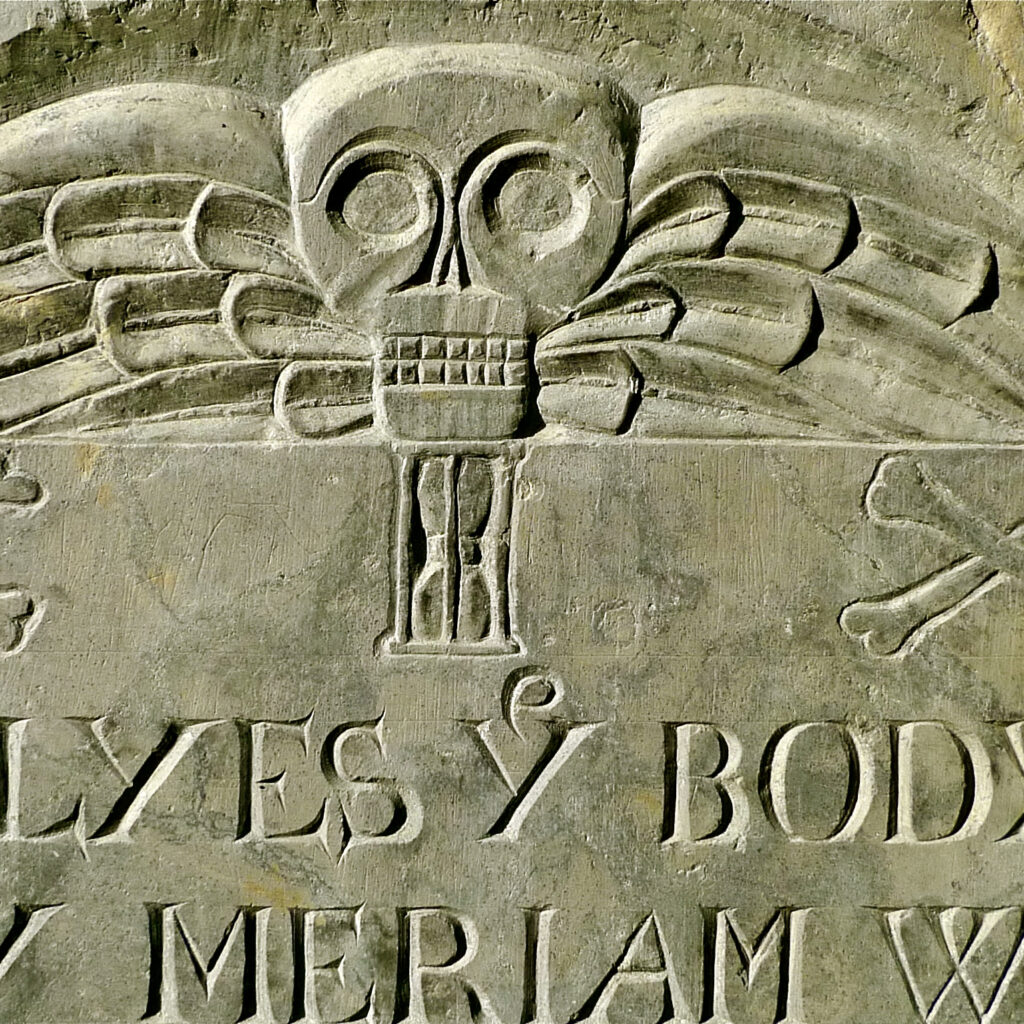

The winged skull joined by crossed bones and ominous hour glass

(“Redeem your hours, my Glass is run, And so must yours”).

Anna Temple, 1753-83, Concord, Massachusetts.

Memento mori (Latin for “Remember you must die”) was a ubiquitous slogan.

Capt. Jonathan Olney, 1709-87, North Burial Ground, Providence, Rhode Island.

The death’s head replaced by a radiating sun.

Providence’s early municipal cemetery, Old North Burial Ground, opened a new section for burials just before the pandemic struck. The availability of many more kinds of stone than the early slate, along with a variety of carving techniques, as well as the engraved photographs and a large range of decorative embellishments, have made for much more colorful–maybe more expressive–tombstones. The number of covid deaths is not just a statistic when so many memorials carry 2020 and 2021 expiration dates.

Brothers Alfonso and Daniel Rodriguez, 2020, North Burial Ground, Providence, Rhode Island.

There is a serious no-nonsense approach to death on the grave markers in Colonial and Post-Revolutionary New England that was rarely surpassed. The premier sculptors of the Gilded Age, Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Daniel Chester French created some of most elegant angels since the Italian Renaissance. Twentieth-century and contemporary funerary angels, however, too often display the mawkishness of a Hallmark card.

Daniel Chester French, The Angel of Death and the Young Sculptor,” Martin Milmore Memorial, 1889. Forest Hills Cemetery, Boston, Massachusetts.

Jane Courtney Mosher-Buyno, 1981-2007. Stockton Springs, Maine.

Opposed to the merely statistical recitations of the number of covid deaths, not to mention the plastic flowers and teddy bears decorating garish stones in the early 21st century, the direct, unpretentious, and brutally honest depictions proffered by Yankee stonecutters show a toughness in the face of the grisly inevitable. They represent a valiant dialogue with death. The historical evidence they provide is witness to the ongoing struggle for which we no longer have an outlet. Remembering that visits to cemeteries were a sometimes-palliative ritual for many generations of Americans, perhaps visiting a graveyard could provide some solace in a time of pandemic.

Halkerson stone, Old Granary Burial Ground, Boston

- The Endless Pandemic: Facing Death in New England - March 19, 2024