Bobby took in everything with those startling, blue eyes; he was only three and a half when we drove from Botswana to South Africa to see a Rugby game. My husband Jason had received word from the authorities that he was finally allowed to do a little traveling there. Being Jason, he had made an appointment with some South African Council of Churches people. We’d already met with them, attended a church service, toured a school in Soweto, and hugged each other out in the open, where the authorities could see.

We could hear the slap and crunch of bodies from our seats in the Johannesburg stadium, and Bobby imitated the sounds: uh! bam!

The Rugby players wore no shoulder pads as if the violence of White on White cleansed a nation of its crimes. At least, it seemed so to me. A camera roamed through the crowd to find the loveliest women and show their faces on a story-high screen. Disgusted, I told my husband, ‘Just like home, back in the ’50s with our parents.’ He was staring at the images on the screen and answered, ‘Huh?’ Then, still looking at the women, said in his charming Jason way, ‘You’re prettier, Ann.’

If they wanted to show me, they’d get an unsmiling face, but never a gesture. I’d not do anything that would put us in more danger than Jason already had.

*

Waiting with Bobby in Michigan, five weeks before joining Jason at his first foreign post in education, I received the news that his work permit had been revoked because he fed coin after coin into the meters outside the South African Council of Churches in Johannesburg so those being arrested inside wouldn’t have their cars towed. Jason, my dear husband, had gotten himself blacklisted from the school in KwaZulu-Natal, where he was going to be the Headmaster and I would eagerly teach sciences. Both of us had worked hard to be assigned to South Africa. Jason and Ann Stevens, American Whites against apartheid.

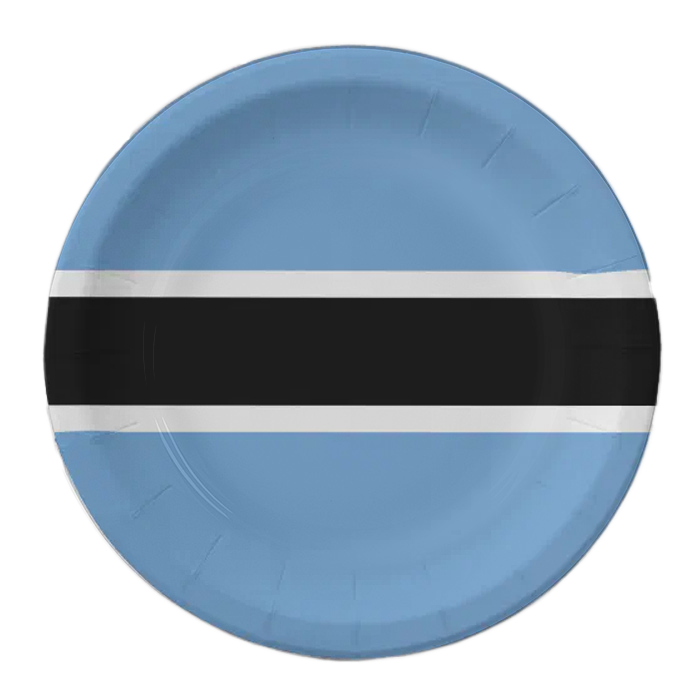

When the church board informed me that instead, we were on our way to the outback of Botswana, I flung dried mixes: grape, lemonade, meat marinades, and desserts into our bags. Would they have drinkable water there? Electricity? I couldn’t find any information on Botswana until I stumbled across a worn book from the 1970s in our local high school. The book called it Bechuanaland, not even Botswana, landlocked and primitive. We were assigned to some outback called Maun, a small village in the northeast portion of Botswana on the edge of the Kalahari Desert. Oh, how I wanted to stay home. I called my absent husband every name I could think of, then I created some. At the tone of my voice, Bobby’s huge eyes stared solemnly over his thumb.

We had been in Botswana for a year, now, trying to learn its ways.

*

After the Rugby game, as the all-white crowd surged up the hill toward town, a young Black woman moved against the flow. She wove through, forcing the crowd to part in a sudden hush. The small green and yellow knitted cap she wore sat askew. Around her shoulders hung an embroidered shawl, faded gold. She grasped at the shawl, though the evening was hot. When she staggered, I wondered if she was on drugs; we all acted as if she were. She was sick, beaten, and hungry. Her eyes haunt me still. Light, almost hazel they reflected the horror of South Africa. Bobby didn’t understand, but he held my hand tighter.

Jason and I walked through the seductive city of Johannesburg with its mansions hidden behind high, protective walls. Street signs boasted of South Africa’s physical prowess in sports—banned though the country was from international competition—as if sheer gall might halt the forces of change.

A drunken clot of men, bristling with sports-fan aggression, veered across the street toward us. One staggered directly at me, his face in a leer. I clasped Bobby closer. Jason put his arm around me and stared the man down as we passed.

“Bastard wanted to devour you,” Jason said.

It was easy to be paranoid. Jason was forever doing something noble, like picking up a scared-looking Black man at the border post from Botswana into South Africa and putting us all through the wringer as South African government officials grilled him, while Jason made his White Savior presence known: all formal politeness but not giving an inch. With Bobby along, I could feel angry at Jason for things like that, even though it made me ashamed of myself.

Why didn’t I reach out to help the Black girl as she passed? But I had to consider Bobby, didn’t I? I didn’t want to bring attention to us. I wondered if my paranoia was an attempt to feel important. But in the next few days, someone might ask Jason and me to carry papers out of Johannesburg into Botswana; take someone with us through the border; help transfer money along. It was the reality for White people.

Jason and I left the crowds and walked the city. Was the Rugby fan’s leer a test? I do know that when Jason split from us to pick up a street-side newspaper, and Bobby and I walked alone for a block, I turned and seemed to startle a White man perhaps ten feet away. His eyes went cold, and he spun around to look into a store window. The window was empty, blackened, and still. The man stared at it, his stocky body rigid in a crisp white shirt and creased blue pants.

“Mommy, why . . .”

“Hush.”

Jason jogged back across the street. I took Bobby’s sweating hand, and we walked toward the beautiful Carlton Hotel where we were to meet a journalist, his wife, and another woman awaiting trial on trumped-up charges. The police had her visa so she couldn’t leave the country.

Near the Carlton, a tall, stooped man, obsidian-black, brushed Jason’s arm. “Sorry, Baas,” the man said.

“I’m not your boss,” Jason said. I was proud of my husband for that. After hustling us through the lobby, Jason leaned heavily against the elevator’s carriage. He jabbed the button for the top floor. Embarrassed, he checked for his wallet.

The elevator to the Carlton Hotel’s restaurant lifted us high above the city. Barked orders of the White maitre d’ to his Black staff gained us a good table at the window where we awaited our guests. We sank into soft leather chairs. Below us, lights shimmered in the alleyways of the city and glowed like smudged candlelight along eight-lane highways. The ruined young woman, the mysterious Black man, and the White bullies faded behind the glitter.

“It looks like Chicago on a clear evening,” I said. Then I turned from the blue sparkle and saw the stocky window watcher enter the restaurant and beckon the maître d’ aside. Bobby laid his head on my arm and closed his eyes. Did he sense my fear? I could taste it.

*

Five days later, having decided to shake off South Africa by visiting key schools back home in Botswana, we drove silently on the desert road to Maun. Bobby had said little as we bade goodbye to friends. Hanging onto my skirt, he’d become a shadow. Even the soccer ball and the safari hat we had bought in Zeerust weren’t of interest. Those sharp eyes had absorbed too much. Bobby and I should have stayed with Auntie Ruth at the mission house in Gaborone, Botswana’s capital; South Africa was no place for a child. But I’d wanted to go so badly, and I didn’t want to leave my boy with others.

When we stopped at the third cattle quarantine and got out to have our shoes sprayed, Jason made small talk with the gatemen, and I hunted for soft drinks in the cooler. “Let him sit in the front,” Jason said. The long trek continued with Bobby huddled in my lap. I tried to interest him in a game of Count the Palm Trees. There never were many trees, but it kept him occupied. An hour more of open plain wore on, and my eyes began to feel heavy. I dozed.

“Look,” Jason said.

Bobby pulled on my shirt. “Look, Mommy.” A mile-wide dust cloud had formed across the plain. Low and dense, it drifted on the horizon like a ghost. It was moving toward us.

“Jason.”

“See,” Bobby shouted. Jason tried to grab him, but he scrambled over the seat to the back, snatching up his new safari hat.

My husband hit the brakes as Bobby threw himself into the front seat and scrabbled over Jason toward the open window. We struggled to hold onto him, none too gently.

“Bobby, damn . . .”

“Cowboys,” he said pointing and squirming.

We had heard of them but were told we’d never see them, not if we lived twenty years in Botswana. Emerging like magicians from the dust, Basarwa cowboys— Bushmen in huge sombreros and colorful ponchos—drove gaunt, slow-moving long-horned cattle from the blistering wasteland of the Namibian desert. Red, orange, and bright blue stripes zig-zagged the wool on their chests, and huge, round sombreros framed yellow skin stretched tight over carved cheekbones. They appeared from the world’s deadliest surface, and the ground rumbled and moaned from the weight of them. Yet they and the long-horns glided past the car in a swirl of hooves’ dust that the wind carried away.

The cowboys shouted, ‘Pula, pula!’ We didn’t know if they meant, Hurrah! We want rain, or Do you have any money? We were enchanted.

Swinging his safari hat with all his might and leaning suddenly so far out the window his dad almost lost his grip on the waistband of his pants, Bobby shouted back, ‘Pula, pula, pula!’ until his voice was hoarse. He screeched an ear-splitting, ‘Yee-ha! Here, cowee, cowee!’ The sharp smell of well-worn saddle, the brilliance of striped colors filtering through chalky clouds, and every line in the faces of those free men seemed to soak into my Bobby’s little body. ‘Pula!’ he screamed.

We were in unshackled territory now.

****

- Bobby’s Eyes: Apartheid 1983 - December 20, 2023